Not All Grasses are Created Equal: Growing Tips

09/19/2012

by: Paul Pilon

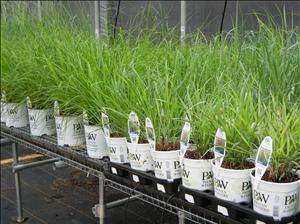

Panicums like these are easy to finish in 1-gal containers

Grasses can generally be categorized into three categories; cool season grasses, warm season grasses, and sedges. These categories correlate with the seasonality or the time of year when they are actively growing. These groupings are also influenced by the origin of the individual grasses. When growers receive starting materials, how they grow them, and their success is greatly influenced by the type of grasses they are producing.

Cool Season Grasses

Cool season grasses are at their prime and grow best when they are grown with cool temperatures (60-75° F). These grasses typically begin to grow during the late winter or early spring and flower from late spring to early summer. The growth slows down during the heat of the summer and many cool season grasses go dormant during this time. Several cool season grasses resume growth with the cool fall temperatures. Many cool season grasses are evergreen, while others may be evergreen in the South but go completely dormant when they are grown in northern climates.

Cool Season Grasses |

Calamagrostis acutiflora, Festuca, Helictotrichon, Koeleria |

Keys to Producing Containerized Cool Season Grasses

Starting materials for cool season grasses should be received in the late summer or early fall when the plants are needed for early spring sales the following year or when they are being grown in large container sizes. Planting them at this time allows for the best bulking as the plants put on most of their growth during these cooler months. Spring planting is usually reserved for production in smaller container sizes as most cool season grasses produce flower plumes fairly early in the growing season and spring planting may not allow enough time for bulking.

Warm Season Grasses

Warm season grasses perform the best when they are grown with warm temperatures (75-90° F). These grasses emerge later in the spring than cool season grasses; growth usually begins in the mid-spring as temperatures begin to rise. Warm season grasses typically flower in the late summer or fall and usually become dormant prior to the onset of winter.

Warm Season Grasses |

Acorus, Andropogon, Arundo, Calamagrostis brachytricha, Chasmanthium, Cortaderia, Erianthus, Hakonechloa, Miscanthus, Panicum, Pennisetum, Schizachyrium, Spodiopogon, Sprorobolus |

Keys to Producing Containerized Warm Season Grasses

Since warm season grasses grow most actively during the warmer months, it is best to receive starting materials from the late spring to mid-summer. For this reason, avoid bringing in starting materials of these grasses in the fall. Keep in mind that warm season grasses prefer warm temperatures for growth and bulking; therefore, if cool temperatures (<60° F) are present, they may need to be grown in a heated facility until they are properly bulked up. Unless significant heat can be provided, avoid planting liners in the late winter or early spring.

Sedges (Carex)

Sedges are a terrific option for customers looking for ornamental grasses that grow in the shade

Keys to Producing Containerized Sedges

Starting materials can be received and planted from early spring through late summer; avoid planting them in the fall. Since many sedges are evergreen and tend to flower in late spring to early summer, it is often best to plant them during mid to late summer the year before they are to be sold to allow adequate time for bulking.

Sedges tend to grow more like warm season grasses; however, they can be grown with slightly cooler temperatures. Additionally, sedges grow slower and are more sensitive to cultural conditions, such as soil moisture and fertility levels, than most ornamental grasses.

Most Carex cultivars (Banana Boat, Bowles Golden, Ice Dance) prefer to be kept moist during production (above average water requirements); however, several cultivars, such as (Evergold), have average to below average moisture requirements.

Production Tips for all Ornamental Grasses

While transplanting, avoid planting the liners or bareroot too deeply or too shallow; always plant to match the original soil line of the liner with the growing mix of the final container. Ensure there are no air pockets and the roots have good contact with the growing mix.

In the landscape, the majority of ornamental grasses perform best when they are grown in full sun. However, in containerized production, many grasses grow best when some shade is provided (35%). Although shading is optional for most grasses, several types of grasses (Carex, Chasmanthium, and Hakonechloa) benefit when they are grown with lower light intensities.

It is important to keep the root zone of newly potted grasses moist, but not wet, until they become established. For container production, follow the irrigation guidelines in the table below for established plantings.

Below Average Irrigation | Average Irrigation | Above Average Irrigation |

Cortaderia Festuca Helictotrichon Koeleria Schizachyrium Sporobolus | Andropogon Arundo Calamagrostis Chasmanthium Cortaderia Erianthus Hakonechloa Miscanthus Panicum Pennisetum Spodiopogon | Acorus Pennisetum |

All ornamental grasses will require more frequent irrigations once they become root-bound.

Most ornamental grasses are moderate feeders and require slightly more fertilization than most perennials. Maintaining pH between 5.5 and 6.3 and feeding with rates of 100 to 150 parts per million nitrogen is suitable for grasses with moderate to heavy fertility requirements. Several grasses (Acorus, Carex, Festuca, Hakonechloa, and Koeleria) are light feeders and should be grown with lower fertility levels (50 to 100 ppm nitrogen).

Conclusions

To increase their successes with ornamental grasses, growers must identify which category of grasses they are growing and plant them at the appropriate times of the year. Proper transplant times combined with planting them properly and practicing good water and fertility management will greatly improve the growth, appearance, and quality attributes of ornamental grasses.

Paul Pilon is a horticultural consultant, owner of Perennial Solutions Consulting (www.perennialsolutions.com) and author of Perennial Solutions: A Grower’s Guide to Perennial Production. He can be reached at paul@perennialsolutions.com or (616) 366-8588.